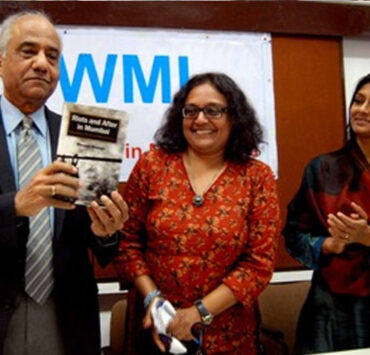

By Kalpana Sharma and Sameera Khan

Sometime in April 2009, an international student studying at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) in Mumbai was gang raped off-campus. What followed was a media frenzy in reporting details of the case. In response to a request by certain women’s activists in the city that NWMI take note of the irresponsible media coverage in this case, NWM-Mumbai organised a meeting at the Press Club on April 25, 2009, with several women’s groups to discuss the media coverage of the TISS student gang rape and the possibility of future action on the same.

Amongst the many issues that came up for discussion at that meeting, one was the idea of having gender and crime sensitization workshop/s with reporters, sub-editors and senior editorial staff of various publications. The NWM group representatives at that meeting (Kalpana Sharma and Sameera Khan) volunteered to meet some senior editors and newspaper staff to explain the implications of irresponsible media coverage in rape/sexual assault cases and also to explore the idea of gender sensitization workshops with editorial staff.

This note is to update you on how we took that idea forward. NWMI members Kalpana Sharma and Sameera Khan initiated a dialogue with three Mumbai newspapers whose coverage of the TISS student gang rape case had been particularly criticized. Of these, two newspapers responded positively to our suggestion that we informally meet up with their staff and discuss the coverage of sexual crimes against women.

At both newspapers, we met a large section of the editorial teams of those newspapers. At one we got an enthusiastic response from the Resident Editor and other top editors. The RE, deputy RE, features editor, political editor, the entire crime and legal issues coverage team (numbering about nine), members of the desk, the person who handles the front page and several others, including a couple of interns, came to the meeting. At the second paper too, the meeting was held in a big conference room and there seemed to be at least 30 people in the room.

We began both meetings by stating why and how we were there, explained the genesis of NWMI, its interest in promoting professionalism and fairness in journalism, the kind of issues that the Mumbai group has taken up – covering war and conflict, using RTI, the Official Secrets Act, reporting on crimes against Dalits etc. It was explained that one of the reasons we had taken this initiative was because of the feedback we had received on the media’s coverage of the TISS rape case. As professionals, we were often asked questions about why the media does what it does. That even while we understand the pressures of competitive journalism, was it possible that certain norms that had always been followed in the past were now being overlooked? That this applied not just to crimes against women, but also crimes involving minorities and other vulnerable groups.

We also pointed out that when women, particularly middle-class women, face sexual violence/assault in public, the media covers it very differently from violence faced by men. Assaults on men never elicit the kind of speculation and details that assaults on women seem to bring on. The excessive concern with the sexual safety of women means we tend to cover this type of crime against women disproportionately, often over several days, often bringing in minutiae and trivia.

In the TISS rape case, although the name of the victim was not reported, there was plenty of material that clearly revealed her identity. Details like the institution where she studied, the course she attended, her course supervisor, the hostel where she lived, the name of her close friend, etc. These details identified the victim to those in her immediate environment and with whom she regularly interacted – precisely the people she did not want to be outed amongst. Was giving any of this information relevant?

Similarly, by carrying part/full FIR, the media not only invades the privacy of the victim (who by law should be protected) but also makes it difficult for other women who get sexually assaulted, raped, molested in the future from coming forward and filing an FIR, from officially reporting the matter, which in case of rape they already find tough to do given the nature of crime and how they are generally treated by the medical/legal system.

As for the legality of publishing an FIR, we pointed out that though the FIR is a public document, in rape cases, where the trial is in-camera, both the disclosure of the judicial proceedings and the identity of the rape victim is proscribed by law under Section 228A of the Indian Penal Code.

We suggested that ideally the FIR if obtained, should have been used as one source of information only, and the information in it should have been used judiciously. We raised the question of what the position of the media should be in such cases. Even if we argue that it is not our job to be sympathetic to the victim, surely we had to be neutral. But if you give information that tilts the scales in favour of revealing the victim’s identity, was this neutrality? If you quote what the accused or their lawyers say, including attempts to besmirch the victim’s character, without making any attempt to give any other side, was this neutrality? Wasn’t this in effect working against the interests of the victim who after all could not speak out?

We offered the example of the Central Park jogger case – in April 1989, a woman on a night-time run through Central Park in New York was violently beaten and raped. It ran as a major media story as the victim was a white female and the suspects were black men. For the most part, the media coverage kept her name and all details of her identity anonymous – simply referring to her as the ‘Central Park Jogger’ for years – neither she nor her friends were identified in any way.

We wondered if there were adequate checks and balances in place in newspapers to ensure that these kinds of things don’t happen. For instance, most senior subs, and editors, are trained to check and double-check dates, figures, designations, spellings especially of names etc. Why isn’t the tone of reports on crimes, or their content, also scrutinised more carefully?

We widened the question to the attitude of the press towards information given out by the police. By and large, this is reproduced without questioning. There is not even an element of scepticism introduced into the reporting. This is particularly evident when reporting on so-called “terror” cases. Press conferences by certain senior police officers, for instance, see hardly any questions being asked. Yet, the police routinely makes claims and then turns around and changes its stand. Does that not require tougher questioning by the media? And should the reporter not make an effort to present information given by the police in a manner that the reader knows that not all of it is completely substantiated but that it is only one version?

A couple of the reporters asked what they should do in cases when there is only one agency that is privy to that information and there is no one else from whom you can get another version. (They were talking specifically on the recent case of Sadiq, a man suspected of being a part of the Indian Mujahideen. A senior police inspector, Rakesh Maria, had stated this in a press conference but recently, the Anti Terrorism Squad told the court that they had no evidence to establish this.) The point these reporters were making, in response to an issue raised by us about single source stories, is what could they do if there was only a single source? How could they carry the police version and yet balance the story? They also said that they could not take issue with the police and get on their wrong side because that way they could be blacklisted and denied information in the future.

Someone asked what details of a victim are alright to give in a story and what details would compromise the victim’s identity. We suggested age, general background (a student, a working woman) as details that would be alright to report but not specifics. One young sub-editor asked whether for instance, they could mention where a victim’s father worked. We responded saying that while a general statement mentioning that the victim’s father was a ‘bank employee in the western suburbs’ was alright, a specific statement saying he ‘worked at a so-and-so bank in Bandra West’ might compromise a victim and her family’s identity.

A more tricky issue that came up for discussion was the latest case (May 2009), of a 13-year-old being kidnapped and sexually assaulted. Some weeks back, an actor had gone public about his 13-year-old daughter being kidnapped. He had filed a complaint with the police but before they could act, she came back. With her, he managed to reconstruct what happened. And it emerged that she had been taken to a remote guest house in Madh by a stranger, the people at the guest house had seen her with the man and raised no questions even though she was clearly a minor. A few days later, when the police reported having picked up a suspect in another similar case, where a minor was taken to a guest house in the same location and the girl had been forced to have “unnatural” sex with the man, the actor got hold of a picture of the man and found that his daughter identified him as the same person. Now it appears this man has been doing this with a number of minors.

On May 21, when the story of the second minor girl came up and rape of minor was added to the charge of kidnapping, it was interesting that barring one paper, which gave the name of the actor and mentioned his daughter, all the other papers referred to him just as “an actor” and wrote the stories carefully so that the identity of the victims would not be revealed. The story had moved from being a story of kidnapping to a story on sexual assault on a minor and senior journalists realized the need to be more careful in identifying victims. Senior reporters admitted that they had taken the initiative to remove the name of the actor from the copy filed by the reporter. This is precisely the kind of check that we had been discussing. But clearly, this had come about only after the stink raised on the coverage of the TISS rape case.

The discussion at the second paper got quite interesting and intense with young reporters, sub-editors as well as senior editors asking lots of questions. In some ways, they seemed relieved to actually have a place to raise the questions, especially as they had been badly criticized for their coverage of the TISS student rape case. They also seemed quite preoccupied with the competition with other publications/TV and the hunt for an ‘exclusive’ story. Here, the concern of reporters/senior editors was that if we do not disclose interesting details about the victim such as that she lived in a particular up-scale locality, her father worked at so-and-so multinational, she studied at this particular school/college, etc (what we would refer to as key identifying details), then how can we really “catch eye-balls” or get more readers to read us. It was felt that graphic details such as this are what attracted readers otherwise the story would get lost in media clutter. “If we water it down by giving fewer details (and make it almost sterile) what is the purpose of covering that incident,” asked one young reporter. Quite a few reporters/sub-editors felt that by giving more details, including the graphic details of the crime/assault, they were “creating awareness among other young girls and their families – they want to know this so they can save themselves”.

In response, we pointed out that firstly, giving out identifying details of a victim of rape/sexual assault was illegal and secondly, there were other ways of creating awareness among readers than merely providing them titillating information, ways which could avoid compromising on a victim’s right to privacy. Such as, after a sexual assault case triggered by the use of a ‘date-rape drug’, you could certainly provide readers with details of what date-rape drugs are, how they are administered, how to be careful etc. Thus, you could inform them in a very detailed manner without compromising a victim’s identity. Use the victim’s story to tell a larger story, we suggested. Also, avoid the use of a moralistic tone in the coverage of such incidents. When you are chasing the same story over several days, there could be a tendency to start doing that, pointing fingers at a victim’s character, why she was out, what she was wearing, stereotyping her and ‘her kind’ etc. Basically in the attempt to “get eyeballs” and compete with other media publications and TV channels, don’t slip up on basic professional reporting do’s and don’ts.

At both meetings, we also shared norms followed by some newspapers abroad with regard to such coverage and the need to re-look at professional norms in our context. Firstly, we suggested the need to have journalistic norms in place – it gives media credibility in eyes of the reader/viewer. Secondly, have those norms known to all on staff/ even inform readers of them. Thirdly, follow them, institute a system of checks and balances that leaves little room for error. Finally, while some of these norms are fixed (such as not disclosing a rape victim’s identity), many other norms are grey areas, some quite fluid and changing depending on the nature and timing of the story, etc and these may need review on a case-by-case (or story-by-story) basis. But it’s important we keep track of them and develop an ever-evolving code of ethics/professional norms for our publications and the media at large.

Based on this positive experience, we are hoping to gradually develop a training module on coverage of gender issues, particularly sexual crimes, that can be regularly imparted to editorial teams as well as media students.

April-May 2009