By Shrabonti Bagchi

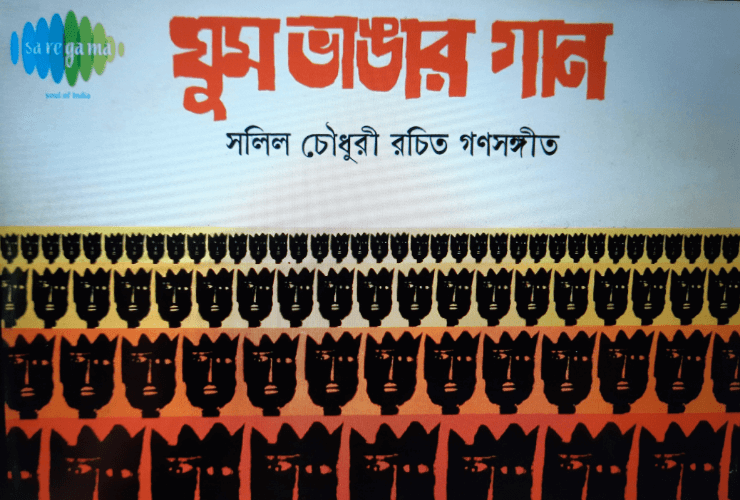

Growing up in a Bengali household in the 1980s, cassette tapes were as essential a part of ‘learning about culture’ as bound volumes of Tagore’s works and novels by Sharatchandra Chattopadhyay and Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay – many of them wedding gifts to my parents at a time when gifting sets of serious books to newlyweds was a beautiful and glorious tradition. Among the many cassette tapes that littered our home, along with Rabindrasangeet and copious amounts of Hindi film music (my mother was not snobbish), was a curious little album called ‘Ghum Bhangar Gaan’ (loosely, ‘Waking Up Songs’). When I was very young, I thought it was a special weapon in my parents’ arsenal to get me to wake up early to get ready for school.

It was only when I was much older that I realised these were protest songs; songs about poverty and freedom and capitalism and activism.

Produced by the Calcutta Youth Choir, a choral band of protest and ‘andolan’ (revolution) music formed by Salil Chowdhury, his wife Sabita, and actor and singer Ruma Guha Thakurta, the album contained songs that mostly went over the head of a 10-year-old. But something of their spirit evidently lingered because I can hum most of them even today – such as the lines ‘jokhon proshno othe juddho ki shanti, amader becche nite hoy nako bhranti, amra jobab di shanti shanti shanti’ from the song Amader Nanan Mote (We are divided in our views, but when the choice is between war and peace, we always choose peace’). It is only now that I understand that this particular song captured an immensely complex and sophisticated idea – that as liberals, feminists, activists and others in favour of social justice, we may have divergent views on a lot of things, but there are some ideas that unite us, and one of them is peace.

Protest songs have been a part of the Bengali cultural milieu since before Independence, and they were mainstream in a way that even a somewhat Anglicised, Enid Blyton-reading, sausages-and-mash craving child growing up in Bihar was not unexposed to them. The protest song riding the airwaves today, Nijeder Mawte Nijeder Gaan, produced by a bunch of actors and musicians from the Bengali theatre, film and television industry, is very much a part of that tradition. It embodies the belief that music can express strong, contrary and complex ideas, that it can stir and move and energise. The day the song was released, someone tweeted that he heard it while driving back from work and had to pull over because his eyes had misted and he couldn’t see for his tears.

It is a powerful song. Without actually naming any particular political party (though the headlines interspersed through the video don’t leave any room for doubt) and released almost on the eve of an extremely fraught election in West Bengal, it is bristling with criticism of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). It doesn’t mince words in calling out fascism for what it is – “Ami Goebbels er ayenaye, thik tomakei dekhe felechhi” (I have seen your reflection in Goebbels’s mirror) – and while it is an attack on fascist ideas and tactics irrespective of time and place, in many ways it is also intensely specific to the present, as when it accuses the adversary of “measuring everything in terms of Pakistan”.

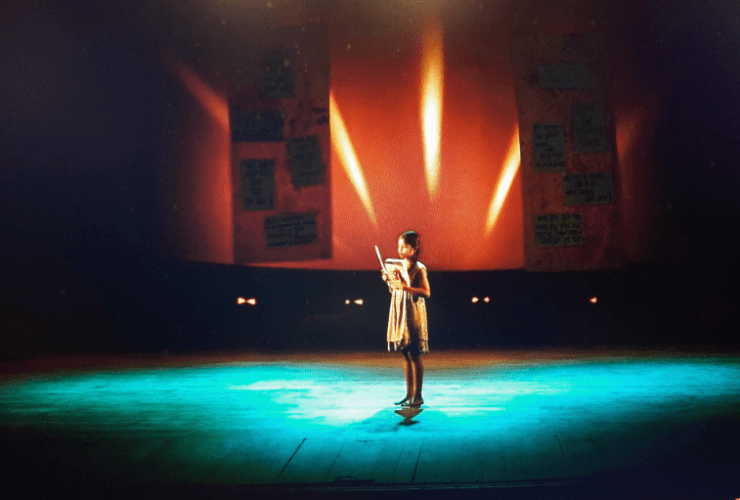

Disapproval of misogyny and support for patriarchy is also revealed in several segments in the video, including one in which a pointed reference is made to the statement of Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath to the effect that women need protection, not freedom, and that their male relatives should “channelise” their energy because “a protected woman’s energy gives birth to great men” (giving birth to great men is of course a woman’s supreme duty). The song ends with a young girl, a balloon seller, coming on to the stage and joining the chorus. As the credits roll, the Preamble to the Indian Constitution forms a backdrop for her silhouette — she is at once the country’s past and its future, the montage indicates. A bit mawkish, some might say, but like the best cliches, it works.

An unfortunate (though thankfully minor) side effect of the song’s popularity is the nudge it has given to Bengali jingoism and exceptionalism. “Only Bongs can do this”, “Only Bengali actors would have the guts to stand up”, “Dude, Bongs have spine” are some of the sentiments one has heard often over the past several days – and one knows this not to be true. Our farmers are still protesting, our activists – from Stan Swamy to Sudha Bharadwaj and Anand Teltumbde – are in jail; very few of them, as far as I know, are Bengali.

But perhaps the sentiment arises from the resentment and disappointment people have felt as their real heroes, and of course by that I mean big Bollywood stars, have abstained from commenting on the growing fascism of the Indian state. Compared to that silence, Bengal’s ‘buddhijibi’ (intellectual) class has, indeed, made a difference with this song, a collaborative effort that cuts across gender and age (though not, alas, caste, as a glance through the credits list makes clear).

But this turn is not new. Salil Choudhury composed romantic songs of immense sweetness, and he also gave music and words to poignant and rousing songs of revolution and protest: “O Alor Pothojatri, e je ratri, ekhane themo na” (O travellers on the path of light, it is night right now, but you can’t stop your journey here).