An interview by guest writers Rishika Bhardwaj & Shireen Vrinda

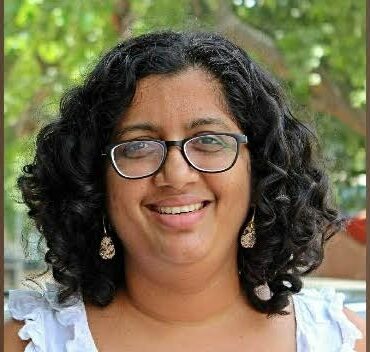

Meet NWMI member Bhanupriya Rao, the founder of BehanBox, an independent digital media start up for gender journalism in 2019. Previously, Rao has worked in data journalism, advocacy and research for over 13 years. As a public policy professional, she has experience in driving social policy change and strengthening democratic and accountable governance. She has worked extensively in building platforms and processes of citizen engagement. She recently facilitated Data: Ek Atmakatha, a workshop for ASHA workers at the Love, Sex and Data conference organised by Agents of Ishq and YP Foundation.

Over the course of this interview, Rao makes the many vital connections between data, gender and journalism. The following are edited excerpts.

What was missing in the landscape that led to your founding BehanBox?

I used to work on rights-based movements like Right to Information, Right to work, Right to Food and such. Then I went on to work with some global policy organizations. One of the things that I found very evident was a lack of the gendered outlook at policy or practice. At Behanbox what we do is try to bridge this gap through our gender journalism. We unpack what a certain policy, act or a law means for women and gender diverse persons. We at Behanbox were one of the first organizations to look at the gendered impacts of the new farm laws. And to make it accessible, more lively and more real for people.

And you also have a focus on data journalism at BehanBox?

When we founded Behanbox we wanted to look at data seriously. If you want to show the scale or evidence that something is happening, it is through data. I am not discounting lived realities at all, we have got to marry both; The lived realities along with the data to show the scale of the issue. Which is why we wanted to look at the data right from the beginning. My previous background aided the process. I used to work on and still continue to work with Open Data. Governments are the biggest collectors of data around the world. There is an entire movement across the world trying to get governments to proactively make data available, transparent, and in accessible formats.

At Behanbox we try to make sense of the data that is available and their gendered aspects. Every election, we break down the data of the participation of women in politics and what are the gender aspects to it, the historical turnout of men and women in these spaces, the number of trans persons participating in elections. We compare it with other states, and countries. We need to push governments for better quality, more timely gendered data. We also need h other organizations to start collecting gendered data, not just in the binary forms but along the spectrum.

How does your background in public policy connect to the work you are doing now?

A – My work started with looking at the gendered data of women in politics. We collected data on how many women actually make it to ministerial positions across states. We found that even this data is not available in one particular place. We collected the data across sites and put them in one place for easy access. When we looked at women in politics, we realised that women comprised 8% or even less in ministerial positions in 2014.

We collected data from 1950 till 2014. Women from states which had poorer sex ratios and were lower in human development indicators had a greater turnout in women’s participation whereas states with higher sex ratio and development indicators had a lesser turnout, which continues to do so even today. When we had the last election in 2019, we started to put out state wise data of women in politics. People found it very interesting!

Why is this intersectional analysis of data important?

Yes, data will show you trends and give you the evidence and not tell you any more than that. But it gives us an incentive to dig deeper. The election data led me to do more ground research. We found a complex web of sexism, misogyny and the overall unwillingness of men to let go of power.

At Behanbox we have written over and over in our ground reports that women who are more vocal or proactive are still not given equal access because of the unwillingness of men to give power. Harassments, violence, and lack of money are all tied to the fact that men do not want to let go of power. The data helps us analyze, even in politics, to continuously report on state elections. When we just collect quantitative data, we tend to ignore the gender spectrums, the reasons behind the analysis of trends, etc.

We have to understand the roles of each of us in the collection of data. The government collects data because a) it has the right to b) it is present everywhere c) it is a part of its mandate. The reason it should collect data is so that it can make sense in policy building and financial allotments, to select where their priorities should be. The methods have become more technologically driven. We get the patterns, a behavior of the cohort, mentioned in government reports. The release of these patterns by the government is done at their own discretion. Organizations like ours play an important role here.

With data journalism?

The important thing about data journalism is that we just don’t pick numbers and write them. Our job is to look at the data, make sense of it and ask the right questions. We just don’t consume data the way it is given to us, we ask questions and verify it ourselves. We look at the behavioural aspect of the data provided. Data journalism is when we make sense of numbers for the people/readers. That’s why we should be careful while consuming numbers and provide caveats.

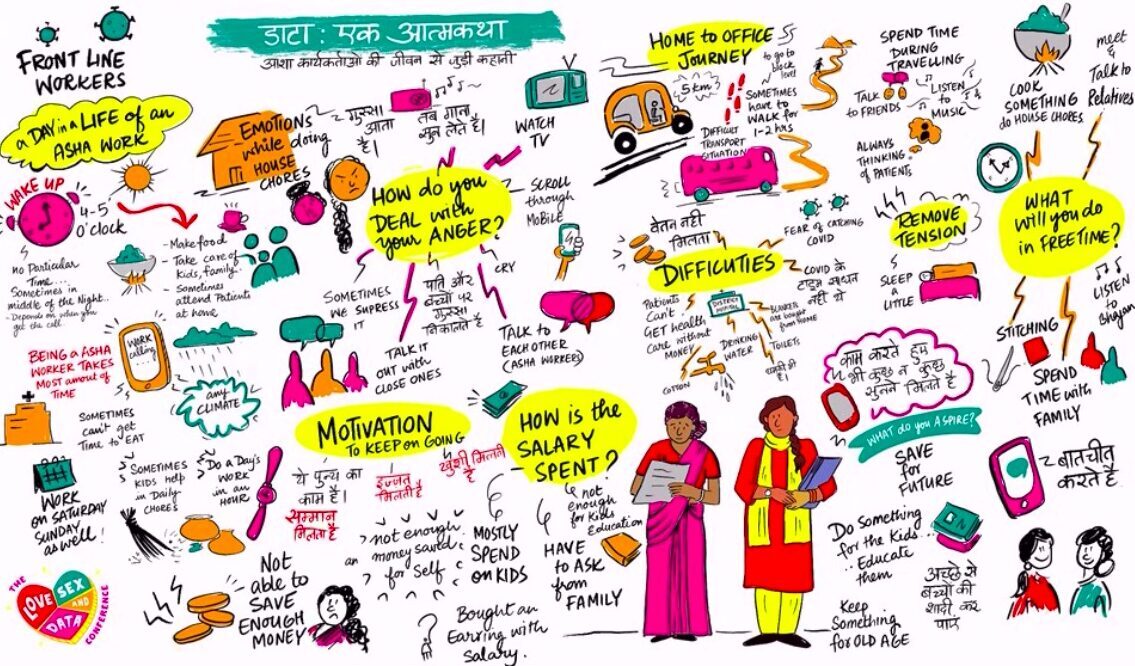

In this context, could you tell us a little about your workshop at the Love, Sex and Data conference, the one you are doing with ASHA workers?

A – Data — Ek Athmakatha is an autobiographical look at data inside the lives of the ASHA(Accredited social health activist) workers. In the case of the ASHA workers, they collect health data in groups and volumes. We wanted to flip the lens through which we’ve been looking at ASHA workers. Making their data personalized. ASHA workers are a crucial part of India’s healthcare system and they often go unrecognized outside of the struggles they face.

We wanted to see what their lives were like and how they divided their 24 hours. The intimacy that ASHA workers have with kids in their own communities brings an individual’s narrative to this data. We want to look at the woman behind the uniform. ASHA workers are embedded in the community, so there is no separate work and social life. We understand the use of their time and emotions and we want to unpack the pleasure side also.

For these two hours the participants step out of their ASHA front and this enables them to think of themselves as individuals, think of their own lives and their own motivations outside of their work. As women who are entitled to these pleasures. While the ASHA workers tell us about their pleasure, a live visualisation of this data by artist Nitasha Nambiar will take place simultaneously. We’re really looking forward to the work that gets released from the workshop

Q – What is your advice to data journalists?

A – Take the data and ask questions. One thing that data journalists should never do is just pick numbers and quote them. In data collection, each institution has a role to play — they feed into each other. We push authorities to take better steps to collect data. We strive to achieve the goal that all data will be gendered data.

Rishika Bhardwaj and Shireen Vrinda are journalism students at St. Joseph’s College of Arts and Sciences, Bengaluru